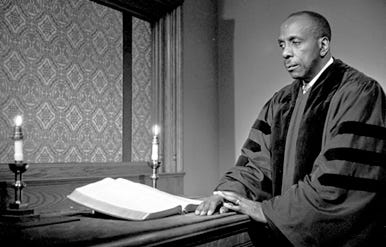

Educator, mystic, speaker, and author Howard Thurman (1899-1981) earned the designation of moral anchor and mentor to the Civil Rights Movement through his teaching of nonviolent resistance which inspired Martin Luther King Jr.

Thurman grew up in segregated Daytona Beach, Florida, attended a black Baptist church, and graduated from an all-black school in Atlanta, Georgia. His first cordial relationships with whites weren’t formed until he attended Rochester Theological Seminary after college. This experience of crossing the racial divide impacted him deeply. One of the lifelong themes of his thinking was the need for breaking down barriers of difference and searching for the common ground of humanity.

In 1944 Thurman cofounded The Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. This barrier-breaking experiment became the first intentionally multiracial, multi-cultural church in America.

In 1971 his last published collection of essays was titled The Search for Common Ground: An Inquiry into the Basis of Man’s Experience of Community. In the forward, he wrote that this book was a formal statement about what had been his life’s work.

From childhood, Thurman experienced a close connection with God through nature and intuited the mystical union of all life. In several of his books Thurman discussed the inward journey of spirituality. From the mystics he learned that we are all connected, and awareness of our unity with God in the Spirit made us aware of our unity with others. For Thurman, social unity flowed out of the unity of the individual with God. Broken unity in either dimension affected the other.

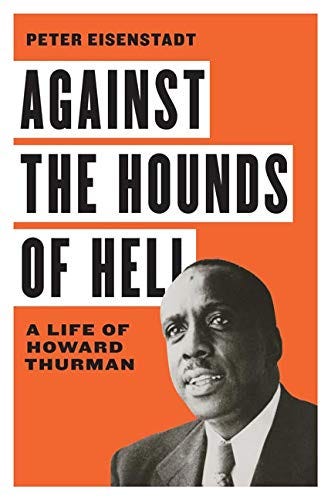

The convergence of his emphasis on unity with his experience of racism made him a fierce opponent of the evils of racial segregation. In his 1965 book The Luminous Darkness he wrote about the scars left on his own spirit in Daytona Beach and in Atlanta. He wrestled with the question of how the dispossessed black human being could maintain his dignity in the face of hatred and oppression. Thurman understood that black people in mid-twentieth century America lived with their backs against the wall, pursued by what he called the hounds of hell – fear, deception, and hate. The hounds of hell threaten to disintegrate the human personality and dignity which Thurman deemed of utmost value.

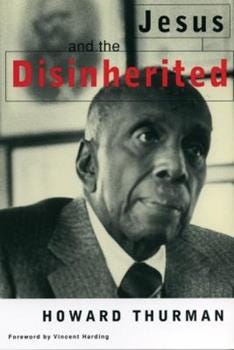

He wrestled with what Christianity, which had been seemingly impotent against racial discrimination, had to say to the disinherited. His thinking on this subject resulted in his most famous book, Jesus and the Disinherited in 1949. He interpreted the life of Jesus, a poor member of a despised, persecuted minority, as emblematic of the life of the Negro in America. Jesus taught his first century followers how to survive in their conditions of oppression, and his message was still applicable for the dispossessed today. Jesus’ death at the hand of the oppressor placed him in solidarity with the suffering blacks.

Thurman believed that Jesus liberated himself, his personality, his dignity, from the hate and violence of the oppressor, and Thurman concluded Jesus and the Disinherited with the statement that what Jesus did, “all men may do.” The religion of Jesus remained liberating. I’ve read this slim book twice!

Thurman understood that the love ethic of Jesus required nonviolence. Thurman was a pacifist, as were many social Christians of his time, but his pacifism would go deeper into a metaphysical category of nonviolence after a trip in 1935-36 to India where he talked with Gandhi, the leader of Indian nonviolent resistance against British rule. Gandhi helped Thurman to envision the possibility for Christianity to overcome the color bar in America.

In his 1979 autobiography With Head and Heart, Thurman recalled a visionary experience while in India at the Khyber Pass where he became convinced that he must demonstrate the power of Christianity to overcome racial barriers. When he returned to the United States, Thurman resoundingly and continuously declared that the means to end the barriers of segregation would be Gandhi-style nonviolent active resistance to oppression. Martin Luther King took this message to the streets in the Civil Rights movement. Some say that he often carried a copy of Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited in his coat.

Coming in May - May 3rd I’ll take a break from Substack to finish the work of the semester. For the remaining weeks in May I’ll be bringing you on a photo journey with commentary through some historic sites in New England!

INSPIRATION

Howard Thurman also wrote poetry. This is one of my favorites and seems applicable today even though it’s not Christmas.

I will light Candles this Christmas,

Candles of joy despite all the sadness,

Candles of hope where despair keeps watch,

Candles of courage for fears ever present,

Candles of peace for tempest-tossed days,

Candles of grace to ease heavy burdens,

Candles of love to inspire all my living,

Candles that will burn all year long.

Here is a link to an excellent documentary about Howard Thurman which has been made available on YouTube: