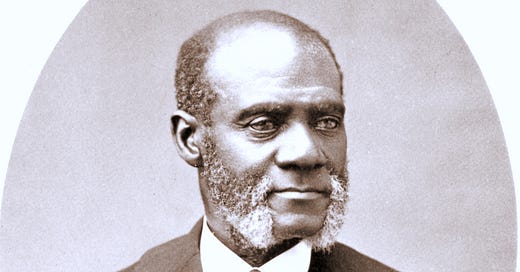

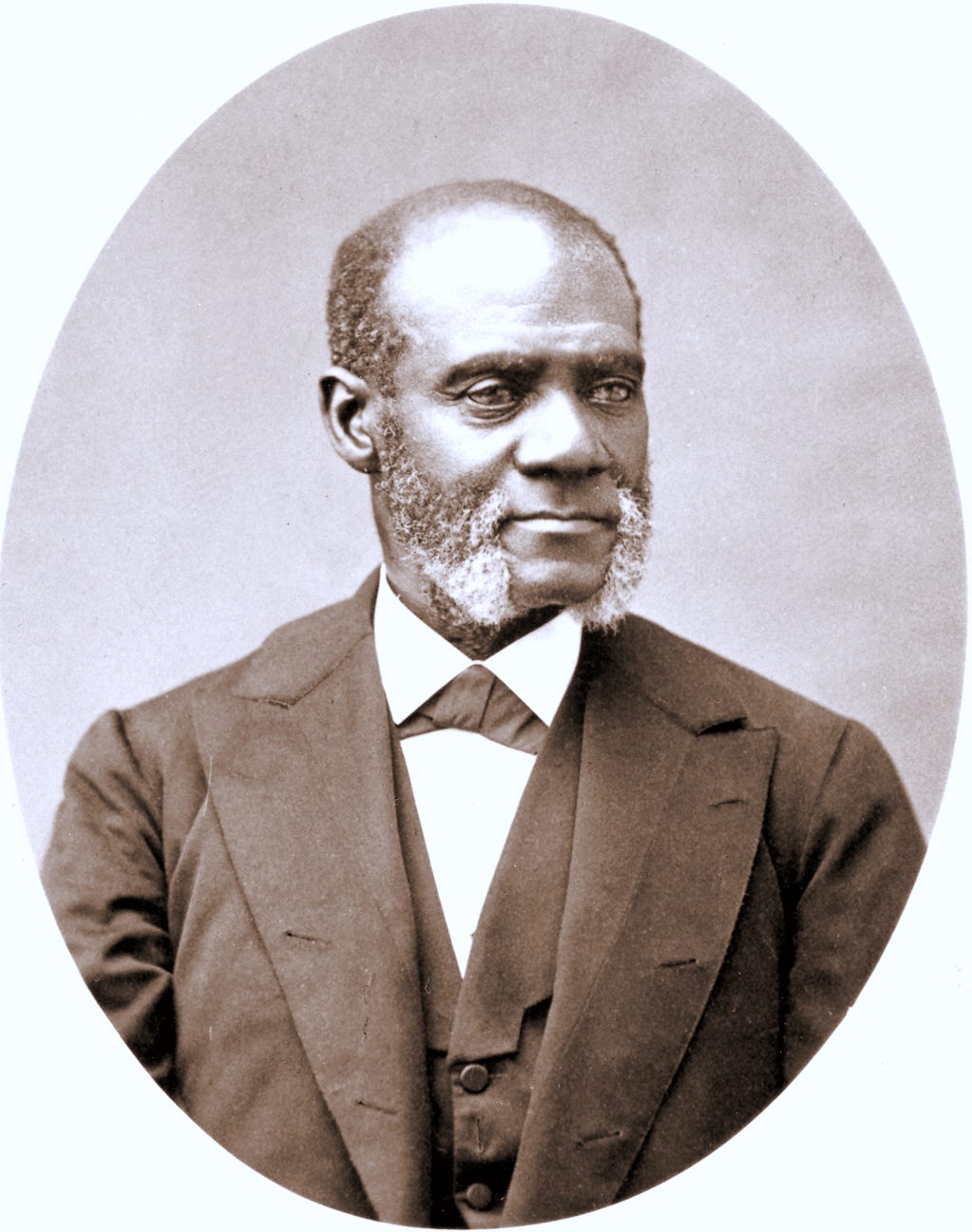

Henry Highland Garnet was famous in his time, but I had never heard of him until last September. My research in the fall of 2021 was devoted to learning about him and trying to understand why he was forgotten. It will not be easy to fill my posts with pictures as usual because of the lack of attention paid to him. But I will share what I can to help you visualize his time and place.

Henry was a strong, bright, and creative black boy born into slavery in Maryland in 1815. His father led the extended family of eleven in a dangerous escape. Henry was nine when the slavehunters mercilessly tracked his family. But with the help of the Underground Railroad they reached freedom.

They settled in New York City, and Henry attended the African Free School, a school established for the children of both enslaved and free blacks.

Henry was a natural leader, and in the African Free School, at thirteen years old, he became the leader of a group of thirteen- to sixteen-year-old boys who vowed never to celebrate the Fourth of July while slavery existed. Even at this young age he understood the hypocrisy.

When he was fourteen Garnet spent some time working as a cabin boy on a ship, and when he returned home from one of the trips, he found his family gone. He learned that a slavecatcher had caught up to them. His mother and father had narrowly escaped, and his sister had been arrested (although she was later released after a trial). Henry came home to no one, but thankfully they were all eventually reunited.

Everything the family owned was destroyed or stolen. Young Garnet went into a rage and used some of his earnings to buy a knife with intent to find and kill the slavehunter who had violated his home. For his own protection his friends whisked him away from New York City out to Long Island. Henry had now lost two homes by the time he was fourteen.

He indentured himself to a kindly captain on Long Island who continued Garnet’s education until age eighteen. Unfortunately, more suffering followed him during this period when he injured his leg playing sports. Severe pain debilitated him in this leg. It was during this time that he converted to Christianity. According to his lifelong friend, Alexander Crummell, “the fruit of affliction…brought Garnet to the foot of the Cross.” Eventually, several years later, his leg was amputated at the hip.

An exciting new school opportunity came to Henry’s attention after his indenture on Long Island ended. He was already nineteen years old but craving more education. Some white abolitionists were starting a school of higher education in Canaan, New Hampshire, near Dartmouth College. The school named Noyes Academy would be racially integrated and co-ed. Henry and two of his friends were among the fourteen black students entering the first class in 1834.

The trip by coach from New York to New Hampshire was brutal. As blacks they had to ride on the top of the coach exposed to the elements. Inns along the route would not house or feed them. People insulted them. And Henry was in constant pain from his injured leg.

They managed to arrive at Noyes Academy and begin their studies, but many of the people of Canaan were angry about this school. One night in July 1835, when all the students were away on a school trip, a mob formed outside the school to stop what they thought of as a colonization of their town by an international throng of black people. Fourteen black boys and girls!

A town magistrate dispersed the crowd, but the next month the crowd returned with oxen. They tied the oxen to the school building and dragged it off the foundation into a nearby swamp.

The students were sheltering in a nearby boarding house and beginning to fear for their lives. Henry starting melting lead and casting bullets. Around eleven o’clock at night horses were heard approaching, and a shot was fired at the house. Henry quickly replied with his own bullets from a double-barreled shotgun. The riders galloped off, and Henry likely saved their lives that night.

But they could not remain in a town like this, so they packed their things and headed out. A mob met them at the outskirts of town. Someone even fired at the wagon they were in. Henry experienced, for at least the second time in his young life, the physical and mental terror of running from white people who wanted him enslaved or dead.

Henry Highland Garnet, by age twenty, had been knocked down by hatred and violence. But he would get up to fight another day.

I’ll be writing more about Henry Highland Garnet. But first a detour next week to look historically at Valentine’s Day!

Questions to ponder: Could you imagine yourself as a radical for a cause? What would it take to radicalize you?

INSPIRATION

“First-century Christians weren’t prepared for what a truly radical and radically inclusive figure Jesus was, and neither are today’s Christians. We want to tame and domesticate who he was, but Jesus’ life and ministry don’t really allow for it. He shattered barrier after barrier.” (From “The Forgotten Radicalism of Jesus Christ” at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/24/opinion/jesus-christ-christmas-incarnation.html)

Sorry I am late to this but so worth the wait! This account made me gasp more than once! And to think this is all in the beginning of this man's life? Wow. As regard to radicalization...if full-term abortion comes to my state like it did to New York, I could no longer sit on the sidelines and be a sweet little Christian. Thank God for Henry Highland Garnet! What an amazing story and I never would have heard it without Peggy sharing.

Thank you for introducing me to Henry Highland Garnet and Noyes Academy! I had no idea mobs in NH we’re just as inflamed and fearful as in the south. Sigh. What a resilient and persistent person Henry Garnet was to overcome such adversity.