How is social change created? The abolitionists of the mid-nineteenth century argued about this. They argued about how to accomplish the end of slavery.

The leader of the abolitionist movement was the Boston newspaper man, William Lloyd Garrison, and he had strong opinions about the way to end slavery. (Last October I wrote three posts about Garrison which you can find in the Archive.)

The Garrisonian way of abolition was to persuade slaveholders through public speaking and writings that their enslavement of human beings was sinful, and once persuaded, they would free their slaves. Garrison refused to advocate for violent means, and he also refused to use political means. He believed the Constitution was a slavery document agreed on by men who were mostly slave owners. In his mind, the Constitution needed to be ripped up and a new one written that guaranteed the freedom of all.

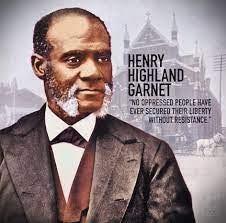

Most abolitionists, including free blacks in the movement, were lined up according to Garrison’s beliefs for about ten years. And then Henry Highland Garnet rose to leadership among black abolitionists. Two weeks ago, you read the story of how this ex-slave was radicalized as a young person.

After he finished his education Garnet became a Presbyterian minister, and then in 1840 at age of twenty-five he offically joined the abolitionist movement. Garnet saw that the abolitionist movement had been going full steam for at least ten years, and nothing had changed.

He decided that people were not going to be convinced morally and that political action was needed. This view put him in conflict with the majority of the movement. But he put all his energies into supporting the new Liberty Party which was formed on the platform of immediate emancipation. More and more abolitionists came to agree with Garnet that political action was needed. In the end, Garnet’s insistence on political means proved correct because slavery was abolished politically by the United States President and legislature.

As years rolled on with nothing changing for the enslaved, Garnet even began to call for the potential need of violence to free the enslaved, a position opposed to by the Garrisonians. At the end of one of his fiery speeches at a black convention, he cried out, “Let your motto be resistance! resistance!” The assembled black leaders were speechless for several minutes. When they recovered, they were in tears wildly applauding.

In the 1850s the militant tone of black abolitionism grew louder in the face of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the 1857 Dred Scott Decision. All of these were laws which revealed a hardening against the possibility of emancipation and black rights in the United States. This was a staggering backlash to abolition. In the end, Garnet’s voice was prophetic because slavery was abolished through violence, sadly.

Henry Highland Garnet was a brilliant orator who gave himself wholeheartedly to the abolition of slavery. Next week, in my last post about Garnet, I will share two moving moments from his life. One was a truly low point for him near the end of the Civil War, and the other was a glorious high point after the war and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment legally abolishing slavery in all the United States.

Question to ponder: Are you with Garrison or Garnet or a different strategy? What are the options for creating change in our own time and place?

INSPIRATION

A ballad of resistance and hope: